Two-year-old Aib Ishaq died in 2020 after prolonged exposure to mold in his social housing association home. An inquest into his death found that, despite repeated reports from his parents concerning the uninhabitable conditions of the property, their concerns were dismissed and the housing association didn’t take sufficient motion.

In response to his tragic death, the brand new laws is often known as Law of Awaab Social housing associations within the UK at the moment are required to “resolve promptly all damp and mold hazards which present a significant risk of harm to tenants”.

This is a positive step towards tackling damp and mold in social housing rental accommodation, which significantly contributes to poor indoor air quality. It also recognizes that constructing occupiers may not all the time take the vital steps to enhance air quality.

Efforts to keep up good indoor air quality often give attention to changing individual behaviors, similar to opening windows, using extractor fans, and running dehumidifiers or air cleaners. While these measures might help, they aren't all the time low cost or effective on their very own. Even when residents are aware that there’s a serious indoor air quality problem, which might have many sources similar to mold, heating systems and constructing materials, they could lack the flexibility to do something about it. This was the case for Aab and his family, because the Social Housing Association refused to act.

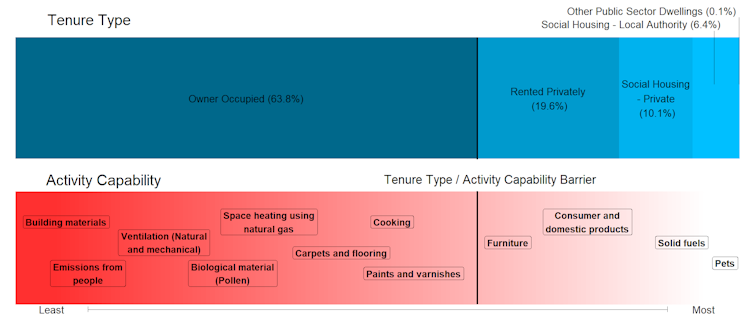

Our 2025 Research paper People's ability—or ability—to make changes to enhance air quality is understood to differ by tenure (eg, private rental, social housing, owner-occupied). In this context, capability refers back to the level of control one has to alter any conditions that affect indoor air, similar to fixing moisture, improving ventilation, or replacing pollution-resistant materials.

The figure below, also from our paper, shows the link between tenure type and capability. The blue bar represents the proportion of the English population living in each period. The red bar below it shows how much control people have over the sources of poor indoor air quality, with probably the most control on the best and least on the left. Each box inside the red bar represents a special activity or source that affects indoor air quality.

Only a 3rd of those activities are accessible to individuals who don’t own their very own homes. Even property owners are sometimes unable to influence larger aspects, similar to the materials utilized in their home or the outdoor air quality of their area. Activities that supply minimal control, similar to upgrading insulation, replacing heating systems, or renovating partitions and floors to remove contaminating materials, typically require significant resources similar to money, time, and space. It is highlighted that when indoor air quality problems are blamed on lifestyle selections, there are lots of aspects beyond an occupant's control.

The AWAAB Act recognizes that tenants face barriers to stopping and remediating damp and mold. It requires social housing associations to reply promptly to all reports of damp and mold, and clearly states that it’s unacceptable to assume that these problems are attributable to the tenant's lifestyle. Housing associations are also prohibited from using lifestyle as an excuse for inactivity.

In the long run, the AWAAB Act will expand to cover other risks that tenants cannot easily control, similar to extreme temperatures, falls, explosions, fire and electrical hazards. However, it doesn’t yet discover other causes of poor indoor air quality, including constructing and decoration materials, heating systems and cooking methods. These sources can emit pollutants similar to Volatile Organic Compounds (VOCs) – Gases emitted from paints, varnishes, cleansing products and furniture – etc A partial case – Small solid or liquid particles produced by activities similar to cooking, heating and burning candles. Both can enter the lungs and bloodstream, contributing to respiratory problems, allergies, heart disease and, over time, even cancer. Subsequently, this contamination might be as harmful to health as dampness and mold.

But, unlike mold, which might often be detected by sight or smell, these contaminants often go unnoticed. A lack of expertise of those pollutants and their sources limits what occupants can do to enhance the air quality of their homes. It is due to this fact necessary that individuals have access to clear details about potential sources of pollution, similar to the products and furniture they buy. If this information isn’t available, the onus unfairly shifts back to residents.

The AWAAB Act is a very important recognition that tenants should not solely chargeable for damp and mold of their homes. This will help protect a few of the most vulnerable people living in uninhabitable conditions, yet it doesn’t prevent other contributors from improving indoor air quality.

Understanding and addressing these broader issues will profit everyone, no matter length of stay. These broader structural aspects include the age and design of buildings, the standard of construction materials, housing regulations, and social inequalities that limit the flexibility of tenants to enhance. Unless these underlying conditions are addressed, indoor air quality within the UK won’t truly improve.

Leave a Reply