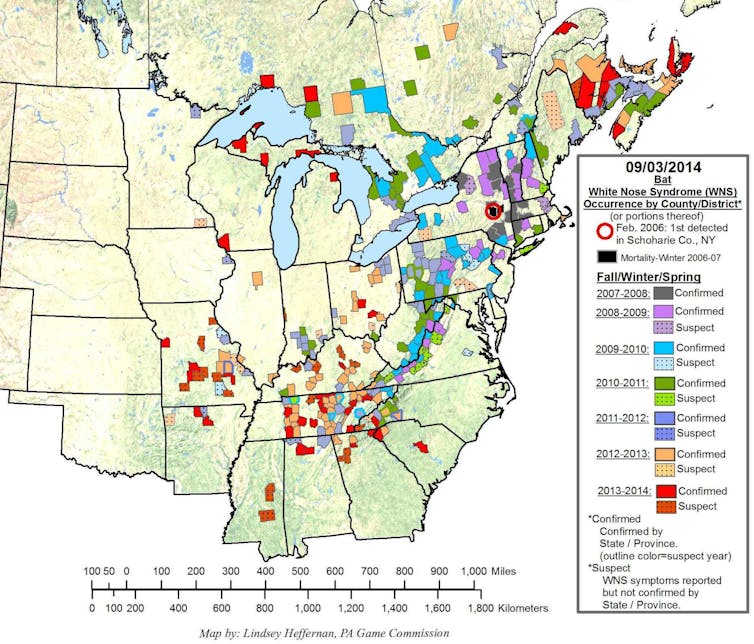

It has been nearly eight years since white-nose syndrome (WNS) was first documented to decimate bat populations in upstate New York. The disease is attributable to a fungus that colonizes the mouth, ears and wings of bats. It is believed to kill by damaging the arm tissues that normally allow bats to manage water loss during hibernation. The fungus repeatedly awakens bats from hibernation, causing them to burn essential fat reserves, resulting in dehydration, weakness and exposure.

Ryan Van Linden/New York Department of Environmental Conservation, CC BY

Since WNS arrived in North America, tens of hundreds of thousands of dollars and countless hours have been dedicated to understanding the disease, assessing its impact on bat populations, and developing ways to mitigate the devastation. Successfully combating the disease has been difficult, but our group is exploring some latest techniques that naturally control the fungus using soil microbes.

CDC

A spreading curse

Fungi have a protracted evolutionary history in soil. It can produce large quantities of nearly indestructible spores called conidia. These spores, capable of live in conditions where the fungus cannot actively grow, be sure that the fungus can survive, and possibly survive. ThriveI A host-free environment – including cave soil in the warmth of summer or previously decimated hibernacula, places where bats hibernate in winter.

Invades North America yearly, killing hundreds of thousands of bats and destroying the tremendous ecosystem services they supply. For example, bats eat so much. Agricultural Insects That healthy bat populations allow farmers to make use of less pesticides on crops.

Several species of hibernating bats have now declined sufficiently to be considered for protected status under the US federal Endangered Species Act. Potential listings could have major financial consequences for North American industries including mineral extraction, forest management and infrastructure development because they would wish to avoid disturbing listed species.

USFWS whitenosesyndrome.org

Human role in WNS

Bat conservation is a small a part of the community's responsibility. Now many Believe It was introduced to North America by human activity – specifically, recreational cavers from overseas using gear that preserves European soil and spores.

This hypothesis is supported by the good genetic diversity of samples taken from WNS-positive hibernacula in Europe. Low genetic diversity In samples from distant areas of the Americas. The fungus has been around in Europe long enough to cause distinct differences between the versions living in regions like Germany versus Spain. The versions isolated in New York, Missouri, and Georgia are essentially the identical, indicating a single introduction of the fungus into the United States.

Additionally, European bats show WNS symptoms, resembling fungal growth on their mouths and wings, but for currently unknown reasons they don't die WNS at higher rates than their North American counterparts.

For bat conservation, this evidence underscores the role of individuals in facilitating and now managing this ecological disaster.

Jonathan May, Wildlife Biologist, Maine Department of Inland Fisheries and Wildlife, CC BY

How to fight back

Developing and implementing control strategies for WNS presents unprecedented challenges in the sphere of microbial control. The nature of bats and the hibernacula where they overwinter introduce seemingly insurmountable obstacles to traditional disease management strategies. Along with harsh conditions and difficult access, bats' sensitivity to disturbance also poses problems. And researchers must continually consider the potential for collateral damage from control agents on native wildlife.

We are searching. for microbes and the naturally occurring antifungal volatile organic compounds (VOCs) they produce as potential biological control agents of WNS. Here's the concept: These bacteria and fungi evolved together of their soil habitat, interacting and competing for resources and space. In this evolutionary scramble for dominance, microorganisms develop traits that increase one's fitness by exploiting the “weakness” of its competitor. Our goal is to harness these natural antagonisms – interactions through which one community member (bacteria) negatively affects one other (fungi) but doesn’t necessarily kill it – within the fight against WNS.

Researchers know that there are soils which have disease-suppressing properties and are fungistatic – that’s, they prevent pathogenic fungi from growing and causing disease, but don’t kill them completely. We hypothesized that these soils may harbor multiple microbial antagonists. And that's actually what we found. VOCs produced by bacteria related to Fungstatic soil Acted as an antagonist against . We also found that a soil-associated bacterium can induce release by vigorous contact. Hostility In the lab – it doesn't need to the touch the fungus or the bat to stop or reduce WNS.

Kyle Gabriel, Georgia State University, CC BY

We at the moment are conducting field trials in hibernacula to explore a possible application method for these microbial controls. We are also investigating the potential of this treatment in regions which are currently at different points within the disease cycle. One site in Missouri is in its first two years after the introduction of WNS, others in Kentucky are in long-term decline.

WNS is here to remain. It is a brand new a part of the North American biosphere and is a cave dweller to which bat species must adapt. No matter what number of powerful tools we develop to combat this disease, they’ll never be enough. Ultimately it ought to be the goal of disease management efforts to reduce drastic population losses in order that enough bats can reproduce to stabilize population numbers. We hope that over several generations bats can develop the flexibility to exist in a WNS world, like their European counterparts.

Leave a Reply