It’s late, the ward is crowded, and the clock is ticking faster than anyone. A health care provider has stabilized the patient higher, but one thing is missing – blood.

A relative is told to “try somewhere else,” and inside minutes, the family is on the phone, calling friends, contacting church groups, posting in WhatsApp chats, hoping someone nearby is qualified, ready and capable of get to the hospital on time.

At this point, healthcare stops being nearly medicine. It’s about networks, trust, and life-saving resources that may be found fairly quickly.

This is just not an unusual drama in Ghana. It is a recurring reality, silently shaping the final result of emergencies, childbirth, surgery and significant illness. Ghana has made progress, however the gap between what is required and what is on the market is wide.

In 2024, Ghana’s National Blood Service Collected 187,280 units of blood. This is far lower than the World Health Organization’s beneficial annual stock of 308,000 units. The consequences are stark, including delays in surgery, difficult medical decisions, and families burdened with in search of blood on the worst possible time.

One strategy to estimate scale is the “blood collection index,” defined as donations per 1,000 people. Ghana’s index increased from 5.9 in 2023 to six.1 in 2024, but is below the ten per 1,000 level that is commonly presented as one. Basic benchmark by WHO.

The opposite is strict. Who are world personalities? The average (median) donation rate in high-income countries is 31.5 per 1,000, compared with 6.6 per 1,000 in low- and middle-income countries and 5.0 per 1,000 in low-income countries. Ghana is a low-income country, yet its donation level is below the typical for this group of nations, indicating a persistent gap between supply and demand.

Why does it matter a lot? Because blood availability is just not a novel issue. It reduces each day health care and becomes decisive in emergency situations.

Few examples are more vital than the birth of a toddler. Postpartum hemorrhage (heavy bleeding after delivery) can progress rapidly, and survival is dependent upon timely transfusion.

In 2025, WHO highlighted that bleeding after childbirth 45,000 deaths Globally yearly. When anemia is common, the danger is even greater: women have less of a physical “buffer” against anemia.

Women who enter labor with severe anemia Seven times the odds of dying or becoming seriously ailing from heavy bleeding after childbirth, in comparison with those with moderate anaemia. Simply put, they begin with less room for error, and without quick access to transitions, things can spiral quickly.

So why is securing Ghana’s blood supply so difficult? Part of the reply is structural. Blood services require investment in collection, testing, transportation at the fitting temperature and distribution networks.

These systems must function reliably daily, not only during crises. Yet demand is increasing with population growth and expansion of clinical services, while resources are limited. The result’s a system that is commonly overstretched, especially outside major urban centers.

Another a part of the story is how donations are consumed. In many settings, stable provision is dependent upon a big base of normal voluntary donors. Ghana continues to be working towards this goal.

In 2024, voluntary donations dropped from 40% to 29% nationwide, even at regional blood centers. Some improvements. This matters because heavy reliance on surrogate donors (relations or friends recruited at point of need) creates unpredictability. An emergency doesn’t wait for somebody to complete work, travel across town, and pass an eligibility screening.

Then there’s trust. People don’t donate in a vacuum. They donate to the system they consider in.

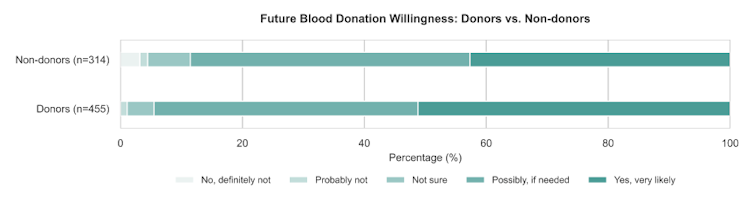

In our ongoing national survey in Ghana on people’s blood donation experiences, trust is clearly concentrated in familiar and formal sources. Nine out of ten respondents report trusting applications coming from a member of the family or close friend, and similarly more trust applications issued by a public hospital or clinic.

Confidence decreases because the source becomes more distant or less verifiable, with clearly greater skepticism about non-hospital community donation groups and probably the most anonymous individuals.

Yet high trust in hospitals doesn’t routinely translate into motion. When people aren’t sure how the blood is used, whether it reaches patients fairly, or whether it may possibly be diverted or sold, consent may be withheld.

Even when people wish to help, uncertainty can result in hesitation: “Will it really go where they say it will?” In a high-stakes context, doubt is expensive.

This gap points to a transparency issue, where trust depends not only on who makes the request, but additionally on whether the system can reliably show where the blood goes.

Finally, communication channels shape outcomes. When a hospital lacks a quick, reliable strategy to reach suitable donors, it falls back on what’s available: phone calls, personal networks and social media posts.

But social feeds are noisy, messages get buried, and never everyone has the identical connections or social reach. The ability to mobilize donors is uneven, depending on who , where you reside, and the way quickly information travels.

None of that is to say that Ghana lacks goodwill. In fact, the other is commonly true: communities respond generously once they understand a necessity and feel confident that their help makes a difference. The challenge is that goodwill alone cannot compensate for deficiencies in infrastructure, coordination and trust.

Telling people to “donate more” is not a technique if the system cannot consistently reach out to donors, support them, and show them that their contributions matter.

The solution?

What would meaningful progress appear like? This starts with strong hospital services and blood bank capability, in order that secure collection, testing and storage can happen permanently.

At the identical time, Ghana needs a more organized digital approach to donor mobilization: a channel that may reach the fitting people, moderately than counting on broad social media appeals that get buried, past, or spread too widely without finding qualified donors nearby.

A well-functioning system can even keep clear, recordable records for each donation and request, making it easier to point out when blood flows and to coordinate a fast, responsive response when an emergency strikes.

This is precisely the gap that our research is addressing. We are developing a hospital connected digital platform tailored for Ghanaian realities. Here, urgent requests may be sent immediately to nearby eligible donors through a trusted channel, with location-aware and follow-up as an alternative of blanket posts. It also builds in transparent, auditable donation-use tracking, helping hospitals coordinate emergencies more efficiently while giving donors clear assurance about where their blood goes.

Because, in the long run, the story of blood in Ghana is just not only about scarcity. It’s about a straightforward query with life-or-death consequences: When someone is bleeding, will getting assist in time help?

Leave a Reply